Demise of the Common Law

SAMPLE READ - First 10% of Book

Sample / Buy a Kindle edition at AmazonCopyright 2012 Edward L. Blanton, Jr.

All rights reserved.

2425 N. Center St, Suite 145

Hickory, NC 28601

www.PenorSword.com

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication nor any derivative thereof may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into any archival or retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright holder and the publisher of this book.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions of this book. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Blanton, Edward. Demise of the Common Law

Summary: Autobiography of Edward L. Blanton Jr. which details the decline of the academic standards in American law schools and the subsequent abuse of the litigation process, aided and abetted by legislative corruption and graft.

1. Common Law. 2. Legislation. 3. Corruption. 4. Litigation. 5. Judiciary. 6. Lawers. I. Title.

Cover Acknowledgements: Adapted from Wikimedia Commons and Kjetil Ree. No endorsement is implied.

Book Design and Production: Studio Kaz, Helsinki, Finland.

LOC : Unassigned - electronic edition

ISBN: Unassigned - electronic edition

Pen or Sword Press (link to Web)

Copyright

Introduction

1. A Challenge

2. At College and University

3. Abroad in the Army

4. "The Law West of the Lech."

5. When Law Schools Taught Law

6. Working With a Wise Judge

7. A Benevolent Despot

8. A Kind Attorney General

9. Accidental Celebrity

10. The 1966 Primary Election

11. Governor Spiro Agnew

12. Missing in Action

13. Changing Partners

14. Governor Marvin Mandel

15. Quelling a Riot

16. Ambassador Louise Gore

17. The 1978 Primary Election

18. Governor Harry R. Hughes

19. President Ronald W. Reagan

20. Wished I Had Said That

21. Fighting Back

22. Governor William D. Schaefer

23. Governor Robert Ehrlich

24. The Loss of the Law

25. After Hours

In Restrospect

Author’s Biography

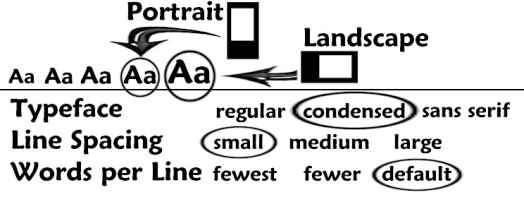

This manuscript has been typeset especially for the Kindle and other eBook readers. Paragraphing has been used profusely to avoid clutter and text overload.

You are free to choose your Text/Format settings, but to maximize the impact and reader satisfaction the following settings are suggested.

Try it out and see.

"The end of a thing is better than its beginning…"

Solomon. (Ecclesiastes 7:8)

Introduction

Although born in a Harper Lee world, I lived my adult life in the Baltimore-Washington metroplex. My story would not be instructive but for the state and national leaders, many of whom were close friends, with whom I worked. I graduated from law school when law schools taught law instead of litigation and dispute resolution. As an idealistic young man, I chose to work in a state where corruption has been a way of life for so long few know the difference between right and wrong.

I turned to politics and did no better, so I put down my sword and picked up my pen, not to expose, indict or condemn but to inform. This memoir shares what I learned from those with whom I worked. We live in an enthralled society, and even worse, we have lost the common law of England.

With the insight old age bestows, many things I did without thinking, or shrank from doing because I chose to live my life free of the publicity the media impose on those who work in the public spotlight, contributed to the loss of the common law, the ‘dumbing down’ of the Maryland Judiciary, and the decline of the Republican party.

Had I stepped up to the plate and suffered the consequences instead of retreating to my own private Eden, the profession to which I dedicated my life would be more to my liking. If you persevere to the end, you will see why I begin by suggesting steps you should take to alleviate the damage I did. I do this because time is of the essence.

As a military officer overseas, a teacher, a legislative and judicial advisor, a lawyer, a politician and pro-bono community activist, a trustee of private charities, a director of publicly held corporations and a trustee of tax-exempt charitable organizations, I had access to public servants at both the local, state and national level.

The critical reader will note how, when and where I failed and why I see myself as the last lawyer. The insightful will read between the lines and detect the factual basis for the conclusions I reached, but more importantly, the ones I hesitate to suggest because I can not prove them in a court of law beyond a reasonable doubt. You need to be aware, however, of the effortless way things are done.

We now live in a world where public schools no longer educate, they indoctrinate. Legislators no longer legislate, they delegate. Courts no longer adjudicate; they abdicate their responsibility to decide, deferring to the bureaucrats who enthrall us and the second and third year law students who do the work they are paid to do.

The oligarchy in Washington decide how we are to be indoctrinated, imposing their will on us through unions, accreditation committees and legislative enactments that ordain what is required of us. By oligarchy I refer to the leadership of both major parties, as tight a band of confederates as the sacred band of Thebes, with similar proclivities.

They alone—the five hundred forty-five in Washington and one hundred ninety-two in Annapolis and eight in Baltimore County—decide what we must do, think, be and pay. Our part-time legislators, jurists and executives ordain we support them for the rest of their lives with multiple pensions earned at every level of so-called public service for the little they do for us and the much they do for themselves, pretending to represent us while actually representing themselves at our expense.

It may well be too late to save the national government, and maybe we ought not try. I live in a house (now over three hundred years old) that was here before the federal government came into existence, and it is becoming increasingly likely, it will be here after the national government is replaced (or scaled back to an affordable level). The impact of the overhaul on Maryland and Virginia (the metroplex) will be severe, not if it happens, but when, for happen it must.

The only part of it we absolutely have to have is what we started with in 1789—the State, Treasury and War (now Defense) Departments. The rest of it is a luxury we can no longer afford, and keeping it will destroy us. States can better decide how to educate their children and provide police, fire and health services. When government pretends it is doing anything more, it is lying, because it can not. Even worse, it enthralls us, eroding our freedom and diminishing the quality of our lives.

When we had no national government before 1774, the people interested in order formed political committees to fight for independence and adopt rules to live by. By and large English in thought, the document they wrote was not a Constitution in the English sense; but a set of by-laws under which the national government operates. When the first one didn’t work, the states elected delegates to a national convention to create a second.

In 1788, wise men insisted upon adding to the constitution ten amendments incorporating the English concept of God-given rights enshrined in their unwritten Constitution derived from the Magna Charta and the Common Law of England, which dates from 1189. It is no accident that liberty first flourished where the Common Law took root.

For years former Maryland Governor William Donald Schaefer and I were entrusted with the perpetuation of a committee formed in 1945 that vetted candidates for executive, legislative and judicial offices through questionnaires and personal interviews, the sole purpose of which was to separate and recommend to voters the fit from the unfit, the authentic from the phony, and those who sought to serve from those who sought to be served. We got good government at the local level for forty years before I tired of it and passed it on to others who let it die. Start there, and until you have it up and running, here are some steps to take to preserve what little freedom you still have. Remember, government is not the enemy, but big government is.

Never elect a lawyer to a legislative body, whether it be the county council, the state legislature or the Congress of the United States. Use your ballot to impose term limits. Never vote for an incumbent elected prior to 2010. Never vote for a sitting or appointed judge or "Yes" to retain an appellate court judge in office. Keep them rotating off the bench.

Insist upon the election rather than appointment of school boards, with the parents in each school district deciding what is to be taught and how much they are to be taxed to support their children’s education. Schools work best when parents are involved.

Insist the lawyer you retain studied law instead of litigation. Make sure his or her degree is from a Jesuit, conservative Roman Catholic or Christian law school that teaches equity as well as law. Deny corporate America the right to indoctrinate the federal judiciary.

Revise the 1789 law creating the federal judiciary by adopting the German model for appointing rather than electing judges, beginning with internships as law clerks and administrative judges and promoting the most able up the judicial ladder. A professional judiciary, insulated from politics and corporate seduction and indoctrination is essential to the restoration of ordered liberty.

To loosen the economic chains, forbid the management of publicly held corporations to nominate directors. Formation of proxy committees to vet candidates is essential if the boards are to serve the stockholders instead of the management class that converts corporate wealth.

Create mutual savings banks, savings and loan associations and insurance companies to originate mortgages, fixing responsibility for credit decisions on the originator. Impose fiduciary duty standards applicable to trustees on corporate management and directors in lieu of the ‘sound business judgment’ rule.

Insist law schools teach and require proficiency in equity, trusts, property, future interests, corporations, taxation, accounting, conflict of laws and ethics before awarding a degree or allowing anyone to take the bar examination. Restore law libraries, legal research and deductive reasoning instead of Lexis-Nexis/Google-like searches. Here is why this is urgent.

The "financial crisis" of 2007 began in July of that year and continued through the first week of March, 2009. There was in fact no financial crisis. Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson and Timothy Geithner, in their ignorance, convinced the 545 there was, because Wall Street lawyers and those representing the Federal Reserve Banks, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, FNMA, Freddie Mac, the FHA, the Congress and the Department of Justice were ignorant of the law.

In 1957, I learned in my freshman class in contracts that a gambling contract is void as a matter of public policy. Neither party can turn to a court of law to enforce it. During the summer of 1958, I took a course in insurance law, and I learned that insurance is not interstate commerce. An insurance contract is a gambling contract. I bet I will die; the insurer bets I will live. I bet my house will burn down; the insurer bets it won’t.

Insurance contracts, notwithstanding their gambling character, are enforced in the courts because they are tightly regulated by the Insurance Commissioner of each state which prescribes the exact terms and the amount to be bet by each party. If the Insurance Commissioner does not approve the contract, it is a crime to sell it. It is gambling that does not violate public policy.

A credit default swap is a gambling contract. A lender fears he will not be paid, so he pays a fee which he calls a premium to a gambler who bets that he will be paid. And the gamblers are not, as you might suspect, necessarily an insurance company like AIG, the principal offender. They are also your bank, an offshoot of a regulated utility (Baltimore Gas and Electric Company) known as Constellation Energy, your brokerage firm, the trustees of your pension fund, or even the trustees of state retirement systems or TIAA-CREF. Not being insurance contracts subject to regulation and enforcement, credit default swaps are unenforceable gambling contracts. Ergo, no crisis: just lost bets no one can enforce, no systemic risk, and the bankruptcy courts—not the taxpayers—efficiently clean up the mess.

Yet, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank Ben Bernanke and his minion, Timothy Geithner, backed by a Goldman Sachs Secretary of the Treasury, terrified a naïve President and a clueless Congress into underwriting unenforceable gambling contracts to the tune of trillions of dollars. A "trumped-up" financial crisis honored unenforceable gambling debts and paid them off with taxpayer money, enriching the wrongdoer in violation of the ancient equity maxim that miscreants may not profit from their wrongs.

In August 2008, I was startled by an overnight decline of fifty percent in the price of a share of Constellation Energy, a significant holding of a trust of which I was trustee. The holding company was the brainchild of my childhood friend and sailing buddy Benard Trueschler, created to bamboozle the Public Service Commission. Reviewing the notes the company’s accountants appended to its certified financial statements included in the annual report for the past three years, I found that the company, then run by an ‘investment’ banker who probably did not know the difference between a watt and a volt, was party to credit default swaps obligating it to pay amounts triple its entire net worth.

The Board of Directors, all stalwarts of the local community, allowed the CEO to gamble with the stockholders equity. Stockholders bailed out in droves, but the CEO negotiated himself a bonus of $18,000,000 payable to his family trust by a predatory corporation launching a rescue effort. If the deal did not go through, the company would pay, with money that belonged not to the investment banker CEO but to the hapless stockholders, $400,000,000, which, in turn, the company collects, by means of its legislatively bestowed monopoly, from the enthralled citizens of Maryland who buy their electricity or natural gas from its wholly owned subsidiary. That is larceny-after-trust, and it is an indictable offense. There is no Maryland prosecutor who can make the case and the United States Attorney is a creature of the lawyer less Department of Justice.

There are others, ranging from county-council persons to the 545, who appropriate public funds to their plush retirement plans. Corporate managers, CEO’s, and Directors who help themselves to stock-holder wealth, should be held to fiduciary standards, as should CEO’s and Boards of eleemosynary institutions, if there is a lawyer left in America who knows that such things existed.

In 2010, Congress, apparently ignorant of the Supreme Court decision that held insurance was not interstate commerce, passed a 2700 page bill regulating health insurance predicated upon its right to regulate interstate commerce. Can anyone today even find the case that held that insurance is not interstate commerce? The same Congress reduced the social security "tax" as part of a stimulus package, unaware that the Supreme Court sustained the Social Security System in 1937 predicated on the fee deducted from employee pay being an insurance premium and not a tax.

If it had been a tax, it would have been unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court made that plain. But today’s lawyers and today’s legislators have no collective memory. Why? Because law schools no longer teach law. They teach litigation and give law students credit for aiding and abetting the abdication of judicial responsibility by interning as law clerks.

We are where we are because more than a century ago, a Columbia University professor named John Dewey set out to achieve social justice through government. Two things stood in his way: the best public school system in the world and a government committed to the rule of the Common Law of England.

The essence of the English Common law and the unwritten constitution of England appear in the Bill of Rights attached to the charter of the government of the United States of America. The Maryland Constitution provides that the people of Maryland are entitled to the protection of the Common Law of England as well as the statutes of England in force on July 4, 1776.

John Dewey’s dream of taking over public education in America was accomplished in the early nineteen fifties, when the supporters of public education finally gained control of accreditation associations of colleges and secondary schools. Ironically this was just three years before a long fight by African Americans to open up access and admission to these very schools, only to find their victory was pyrrhic, for the public schools had already embarked on a long, downhill descent into mediocrity from which they will never recover. Increased funding does not help; it makes the problem worse.

In the eight years between my graduation from Baltimore Polytechnic in 1949 and my return to the public schools as a mathematics teacher in 1957-1959 in the same school system, the signs were everywhere. Teachers had become baby-sitters, and tenure depended upon not confronting trouble makers and passing every student, whether or not he or she could read or solve x+2=6.

Dewey’s disciples expanded their control to colleges and universities, both public and private. I graduated from law school at the University of Maryland in 1960, the same year the proponents of critical legal education (known as the "crits") seized control of the faculties at Harvard and Stanford law schools. With the exception of a dozen or so law schools, every law school in America now teaches that the law is not about justice but dispute resolution. There is no right or wrong; just good argument and bad argument. Crit infested law schools teach the adversary system and litigation. They do not teach law. Judges see a fraud on the Court as ‘good lawyering.’

People yearn for justice. Disputes can be settled with guns and knives. But the law is supposed to settle conflict based upon fixed and unalterable rules to which all adhere. We live in an age without the rule of law, for the law is lost, buried in books no longer on the shelves but supposedly in the computer data base. Law libraries in county court houses are replaced by computers. Legal research by tutored minds is a lost art.

Maryland is the canary in the coal mine. In 2009 the adult population was 4,160,620. The Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation posits that 3,030,064 Maryland residents were employable, of which 954,064 were on Federal, state or local payrolls; another 695,336 were over age 65 (potentially recipients of Federal social security checks); 854,345 were receiving disability payments and 7.1% were unemployed and receiving unemployment benefits. Do the math: 2,718,940 adults in Maryland are beholden in one way or another to government largesse for all or part of their income, collected from the 1,441,660 adults working in the private sector. The enthralled minority are taxed to support the mendicant majority.

Voting results in the 2010 general election in the three Federal District bed-room counties and Baltimore City and County –where the majority of government workers and mendicants live—were heavily Democrat; the remaining eighteen counties were heavily Republican. Is it any surprise that Maryland taxpayers are facing even more burdensome tax increases from a legislature controlled by the Democrat party, regularly meeting in special sessions to increase taxes semi-annually?

Fifty years ago the chief judge on the Maryland Court of Appeals, who was in fact a lawyer and not a bureaucrat, opined that no man and his property were safe as long as the Maryland Legislature is in session. True, but laws passed by city and county councils, state legislatures and the Congress can be repealed by their successors. Bureaucracies running amuck need not be funded and government workers can be fired and their pay and retirement benefits reduced. Can it be done peacefully when the majority is on the dole? As consigliore of the Maryland Republican party for quarter century, I don’t think so.

A vastly scaled down national government is the only way to free us from the military-industrial complex President Eisenhower warned us about in 1960. We must control spending by bringing government employee salaries and pensions into parity with private employment. Pensions part time legislators vote themselves and the bureaucrats they employ should be abolished and those enacting them banished from public office.

Maryland is a lost cause, and it appears that Virginia will soon follow. Between Washington in the northeast, the Navy in the southeast and the Valley in the west populated by students, the Old Dominion is near enthrallment by the mendicant majority. We can no longer free ourselves, and we must appeal to the voters of the remaining forty-eight states for help. How? By curtailing the power of the national government.

Western governments, such as our own, have made promises beyond their means. Debts that can not be paid are discharged by bankruptcy, and when a nation defaults, the government inevitably collapses and must be replaced. Such was the case at the end of the American Civil War. The Confederate South was a nation defeated in war, left without an effective government and impoverished by financial collapse. There was land and labor to work it but no capital to pay wages. The South invented share cropping, and it is still in use today. American ingenuity is turning back to a variation—bartering and issuance of local scrip. That is what we will all soon face.

Chapter 1.

"You are a young man who will make your mark on the world."

—Mayor Theodore Roosevelt McKeldin,

August, 1945

A Challenge

At the close of a summer day I sit alone warmed by the fading sun sinking behind a wall of dark-green evergreens framed by the light-green grape vine embracing the fence around my tennis court. The same light-green seeps between the shadows on the gently sloping lawn sweeping down to the fence beyond which my horse grazes, swishing his tail and flexing his shoulder muscles to deflect late-lingering flies.

In front of me, tall evergreens beside a white, Chinese-Chippendale fence reflect in the still, pale blue water of the pool, beyond which three distinct clumps of trees stretch skyward. The nearest, shading Rattlesnake Run, grow just beyond the far fence of my pasture. Midway up the hill the tops of a large stand of pine hide the pond impeding the flow from the spring which, a century ago, supplied water to my house. A majestic blue heron rises above the trees, large flapping wings slowly propelling him to his accustomed perch on a branch of a dead, honey locust tree.

Beyond the pine encircled pond is the deciduous forest on the hills at the foot of Long Green Valley, green now but soon to display the rich earth tones of autumn. The dissonant chorus of bird calls, frantically protecting their chosen space in the gathering gloom, diminish as the sun sinks, now just a golden glow in the trees between me and the hayfield. I await the quiet night at peace with the familiar scene where I like to sit at the end of my day.

The house behind me is more than three-hundred years old, and a half-century of work has left me spent, but I trust my stewardship will keep this pleasant prospect as it now is for others to enjoy for centuries to come, if indeed those who come after me to this place have centuries to come. It is because I fear they do not that I am writing this memoir. It is a confession of my complicity in your enthrallment. Thrall is a synonym for slave and it was I who may have put you there by the things I did and the things I failed to do.

I am old now, past eighty, but I came here as a young manin 1965 with my pregnant wife and two children, not knowing then I would stay so long or that my life would take the course it did. I came into the world far from here, too long ago to remember, in a house not unlike the one behind me, owned by my mother in North Carolina, overlooking the pond that gave Hope Mills its name.

My mother marched in the vanguard of modern American women, employed at age eighteen by the Southern Bell Telephone Company to go into surrounding towns and rent space for a switchboard, hire and train young women to be telephone operators, politely asking the fortunate few who could afford them "Number, Please" and plugging the line with the lit light into the hole with an unlit light assigned to the person being called.

She inherited the house in which I was born from her father, whose picture hangs in the house behind me now known as Avondell. My grandfather, John Bunyan Bullard, was dead at twenty-four, beloved and mourned by a large family of siblings who fought over his possessions. My mother was two when he died, and but ten when her mother followed, after which she lived with my great aunt Johanna, my grandfather’s older sister, on the campus of Trinity College in Durham, now known as Duke university.

My father lied about his age to join the United States Navy in 1916 and served as the radio operator on the USS Arizona, sailing through the Panama Canal to Peru and Hawaii. He won the Pacific fleet light-weight boxing championship. He married my mother in 1926 and they moved into my mother’s house overlooking Hope Mills, with twenty-two bird dogs belonging to my father and the army officers who hunted quail and played polo with him. My father trained the dogs for field trials in Tennessee, where they did so well they were often stolen by traveling men from South Carolina who plague me still, wanting to paint my neighbor’s barn.

There were Lumbee Indians on my mother’s farm, and three of them worked in the house. One was my nurse until my mother discovered her chewing my food and transferring it from her mouth to mine as a robin feeds her young. I have the vaguest recollection of watching the laundry being done outdoors, wood fires under three large black pots: one for soaking, one for boiling the clothes in soap, and the third for rinsing. I watched clothes moved from pot to pot with wooden ladles, then hung on lines to dry, flapping wildly in the wind.

I have not a lot of memories there, for I was taken to Vero Beach until it was time for me to start to school. I became a law-breaker early, filling the cups in the greens on the golf course beside our house with sand I found in the traps, and drinking home-brewed beer made by the German grounds-keeper who discouraged my play and protected me from irate putters.

Florida was not a healthy place in the 1930’s, and my mother and my sister Millie came down with malaria. Mountain air and no mosquitoes were prescribed, and father moved us to Princeton, West Virginia. The snow was over my head, and being marooned was a welcome respite until a chattering neighbor cleared a path to our door. I dropped a piece of coal a dump-truck left in an outbuilding on the head of a boy I did not like. He survived, but I feared for my own life after the switch I was sent to cut for my whipping proved too limber to break.

When the curative mountain water had been drunk, the pure air breathed and the tropical malaise overcome, we returned to North Carolina, not to the house where I was born, for it had been reduced to ashes on a cold, wind-swept November night when the housekeeper went to bed before it was safe to close the damper in the fireplace. She put the ashes, some still red, in a cardboard box on the wooden porch just outside the door.

The house where my ancestors entertained their Connecticut cousin in Sherman’s army was no more. You may read about it in my novel Grasping the Wind: the Worth of a Word. So we lived for a few months in a boarding house on Bogue Sound in Morehead City. It was there I began my day as I still do with orange juice and fresh chilled cantaloupe. It was also there I learned to sail cat-boats in the safe waters of the sound, separated from the white-capped waves of the Atlantic by a spit of sand on which I often beached my boat and waded ashore to find starfish and sand dollars to stuff in my overall pockets.

An ideal summer passed quickly, and the house my father rented in New Bern was ready for us in September. It was here I abandoned my criminal ways to start life afresh. It was just in time, for it was while living in the bungalow on National Avenue that I first attracted the attention of the trash collectors and a girl who liked me.

New Bern sits on the point of land where the Neuse and Trent Rivers come together, not, as they say in Charleston, to form the Atlantic Ocean but just to make a bigger Neuse River. Having been captured early on by the Yankees in the War for Southern Independence, who held it in spite of heroic efforts by the Confederates to get it back, the houses and churches were not burned and the once-upon-a-time royal capital of North Carolina was and is still a charming town.

I started my schooling at the Riverside School, to which I walked every day from my house near the cemetery for the Union dead. I passed the house of Representative Graham Barden, and I heard my father tell my mother that he was chairman of a Congressional Committee in Washington that parceled out tax dollars to those who voted for his party. He had a daughter named Aggie, and she, not yet old enough to go to Riverside, played in her yard under the watchful eye of her nurse.

I heard Adolph Hitler shouting on the radio in far off Germany, but I had no idea what upset him so. A friend of my father’s was going into a risky business, and he wanted my mother to put up ten thousand dollars for ten percent of it. I heard this as I sat at a small table in the kitchen, eating my supper with my younger sister Faye. The door to the butler’s pantry was open, as well as the door to the dining room, so my mother could make sure we ate our peas and used our knives and forks.

The business was going to market "Pepsi" concocted by a local druggist. My mother was certain a copy-cat drink would not be a success. We drank beer and wine, and "soft-drinks"—which my Negro friends called "dope"—were not found in our pantry. My mother wrote lyrics to sad love songs, which she later heard on the radio after her agent took them as his own, set them to music and released them on big, black 78 rpm phonograph records.

There was going to be a celebration of the first English settlement in America on Roanoke Island in 1587. One wing of Governor Tryon’s palace still survived in New Bern, and it was decided that Aggie Barden and I would lead a troop of other children in a minuet on the lawn in front of the palace. I did not know Aggie, but I was told she had made it a condition other participation that I be her partner. You may read about Tryon Palace in my novel Tory Terror.

I endured black, patent-leather shoes, long-white socks, blue-silk knickers, a lacy shirt and blue-silk jacket from which my doily like sleeves and collar stuck out. We practiced the dance forever to make sure every step was in sync with the music. My teacher sang the words and hummed the tune as she taught us the steps. The urge to drag Aggie to the Neuse River and drown her came to me more than once. To avoid practice I hid behind the garage sitting on a pile of boards, only to be turned in by our neighbor’s servants, who wanted to know why that little white boy was sitting behind the garage all morning.

There was a lot of cork floating in the Neuse. It was used to line the caps of the Pepsi bottles. Some pieces were big enough to use as boogey-boards. Bereft of my beloved cat-boat, I paddled around the Neuse on chunks of cork whenever I found the river free of the water moccasins that crawled in the caves my older sister’s boyfriends dug in the fields next to Mrs. Hartsell’s garden, which she modeled on the kitchen garden at Tryon Palace.

It was not the Tryon Palace garden that attracted me, butthe library in the surviving wing, with its leather-backed law books from the eighteenth century which the Governor used to decide what was right and what was wrong. Now I model my garden after hers and my library after his. And it was from there that I set out to make my life’s work righting wrongs to atone for my criminal past.

My mother tried to right wrongs as best she could. I was often called down from the pecan tree in the backyard to the kitchen table to eat dinner with visitors, white hair crowning their chocolate faces, telling me how things were when they were my age, before the Yankees set them free. At first I thought they were distant relatives, for they were introduced as Auntie this and Uncle that. The titles were a sign of respect because they endured to the end, as St. Paul urged us all to do. They shared their faith-based wisdom with us. My mother told me the South lost a war, and we had to stick together to work our way out of it.

I had one aunt who was real, a half-sister of my mother, who was going to college in South Carolina. She came to visit and it was never Christmas until the taxi dropped her off at our door to laugh the night away. She said the driver told her the Christmas tree in our dining room window was the prettiest one in town. Aunt Ethel walked us to the First Presbyterian Church where kind ladies gave us red-mesh stockings filled with penny candy on Christmas Eve.

Every night before bed-time my mother called us to the alcove by the piano to read from Hurlburt’s "Story of the Bible" after which she asked questions to make sure we had listened. I knew there were places called Jericho and Jerusalem before I knew there was a city called New York.

I liked maps and studied them, so I could find my way home if I was ever lost. There were maps of the places she read about. I knew Galilee was north of Jerusalem but the disciples were always going up to Jerusalem. I thought they didn’t know north from south, for the two most important things I had learned was north was up and south was down. When I went to Israel as an old man, I realized "up" referred to altitude in a vertical, not a horizontal sense.

The rants from Hitler were heard more often but there was less fear in the house when my mother listened to fireside chats from a man named Roosevelt, a name that sounded like the stuff my Sunday hat was made of. He was a Yankee, a good one we could trust, like the cousins who stopped by her house near Hope Mills for dinner while my father’s ancestors set up an ambush at Bentonville.

I thought Roosevelt was a salesman, like my mother’s cousin who astonished me one day by driving up to our house with a Ball canning jar, all lit up and big enough to climb into, stuck in the rumble seat of his car, with peaches as big as beach balls stuffed inside. My mother said his car reminded her of the white Chrysler convertible she drove until my father, lost it in the same poker game in which he won a pair of polo ponies. Too bad Pinehurst was so close to Hope Mills.

Just as school was about to start there were maps on the dining room table and talk of a place called Hickory. It was all the way across the state, and there were more Republicans there than Democrats. We had to go there because there was more money there. My sisters and I sat in the bed of a pick-up truck all the way from the salty tidewaters of the Neuse to the clear cold waters of the Catawba, teaming with bass, crappies and perch.

We shared a huge Victorian house with rounded towers, porches and balconies on a hill at the end of Seventeenth Street with an old lady who spent the winter in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. She promised me oranges and alligators when she returned in the spring. My laughing Aunt visited us here as well. She said there were more millionaires per capita in Hickory than any other city in America, including New York and Hollywood. When I doubted it she explained ‘per capita’ to me, my first introduction to the idea that figures don’t lie but liar’s figure. It’s the basis for equal pay and equal opportunity.

I walked everyday to the Oakwood School, and if we finished our work on time, our teacher read from ‘The Secret Garden." It snowed in Hickory, but my mother had hot chocolate and warm oatmeal cookies waiting when I got home if I waited patiently until she heard the end of a radio program called ‘My Son and I.’ It made her cry, but so did the lyrics she wrote, more so when she heard them on the radio.

There was a row of cabins behind our house, and a large barn between the house and the cabins was being converted into a house for Sam and Hannah Jackson, who reminded me of my New Bern Aunties and Uncles. All of the rooms were being finished in knotty pine which I helped brush with stain. Sam wore suspenders and was almost as dignified as Hannah, who wore elbow length gloves like my mother’s and broad brimmed hats when they went to the Baptist church. At Easter, Sam filled a galvanized wash tub full of dyed Easter eggs for me and the children from the cabins.

On Saturdays the selling ladies came up the hill with fruit, vegetables, and cookies that melted in your mouth, sold from the back of an ancient roofed-over pick-up with a scales dangling from the back. My mouth watered as I watched the scale with some fear, for things were sold by the pound and money was scarce. I heard my father tell my mother he was down to his last dime. So I went out to pick as many blackberries as I could carry, and my mother made them into a pie.

A few days later, I walked down the hill to pick up the newspaper and the bold-black headline said "France Falls." There was a map, and I looked at it and found that Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg had fallen as well; to something Hitler had called ‘panzers.’ The phony war had suddenly become real, so I looked at the date to make sure I remembered it was May 10, 1940.

On Saturdays I took a nickel and went to the double-feature at the theatre with Harvey Geitner and Joe Petree. We saw a cartoon, an installment of the "Green Hornet", and two movies with Guy Madison, Bob Steele or John Wayne always getting the bad guys in the end so we could go home happy. The "News of the Day" showed London being bombed and German paratroopers falling on Crete.

Harvey was in my class at Oakwood, and we roamed the woods and streams behind his house catching snakes, prettier than and not as mean as the cotton-mouths in the Neuse. There were beautifully decorated copperheads that were nearly inert, the laziest snake I ever saw, as well as king snakes, blue racers, and timber rattlers. A hall in Harvey’s basement was lined with wooden cages with wire-screen lids and sides. We lifted the lids and dropped the snakes inside, feeding them a live mouse or a live frog once a week.

To catch them we sharpened the ends of a forked stick with our pen knives. I penned their heads to the ground while Harvey grabbed them by the tail. When I pulled up my stick with one hand, he dropped them into a burlap bag I held open with my other hand and the stick. When we got too many, we would match up an unwanted rattler with a king snake in the sandy road between the Shuford’s swimming pool and Harvey’s house. The king snake always won, and I feared I might be back sliding to my criminal past. So I studied my Westminster Catechism all the harder, got gold stars from my Sunday school teacher covering the numbers of all the questions. I earned a New Testament from the First Presbyterian Church.

In the fall my father bought a new car, a Pontiac—blue onthe doors and gray on the roof—the first two-tone car I had ever seen. He bought some bird-dogs and assembled a portable fence for them. Sam found a young man living in one of the cabins to bring two mules and plow a large garden behind our house for my mother. I helped her prepare the soil, plant the seeds and dig out the weeds. I still garden far more than I should.

I wanted chickens, and there was a shed in the orchard where they could stay, so my father got a portable fence, taller than the one he made for his bird dogs, to keep my chickens safe from predators. They were all white, until my mother cut their heads off to fry them for Sunday dinner, which had to be finished on Saturday after my double-features, for no work could be done on Sunday. I went to my chicken coop to get eggs for the cold potato salad we ate with the chicken. A black snake was curled up in one of the nests. He swallowed an egg I didn’t get to quick enough.

Our Republican neighbors were voting for a man named Wendell Willkie. Their son Joe told me that Roosevelt was trying for a third term so he could become dictator of America just like Hitler in Germany. Their cook was a Republican woman named Bill, who called me and Joe in from our hiding place under the fig trees by shouting "Hot Biscuits" out the kitchen door. When I asked her if she wanted Roosevelt to be a dictator she said her people were Republicans and they were going to help the white folks put a stop to the Democrats trying to destroy our Republic. It cheered me up to know we were all in it together.

In the spring of 1941 I had a chicken sitting on eggs, and I looked forward to seeing the little chicks emerge. But I came down with the mumps, missed some school days, and before I was well the trees were green, the sky blue, and the chicks pullets. It was the only time I was ever sick in bed until my internist had to give me up to surgeries. I was not sick then, just recovering from sloppy knife work.

One Sunday afternoon after Thanksgiving my mother drove me and my three sisters in the two-tone Pontiac east to Statesville to bring my father home. My mother’s song ‘Someday Sweetheart’ was playing on the car radio when it was interrupted by a special news bulletin. The Japanese, who made cheap toys and tiny tea sets for my little sister, had bombed Pearl Harbor.

My father went to Raleigh to see about getting back in the navy to teach the Japanese not to attack on Sunday morning when everybody was in church. The Arizona was sunk and with it the plaque honoring my father as a Pacific Fleet boxing champion. I knew then why I always got boxing gloves and punching bags for Christmas when what I wanted most was a Red Ryder Daisy air rifle and a Bowie knife.

There were firecrackers at Christmas as usual, war or no war. My sisters got new bicycles, which I knew they would because I watched them being delivered to Sam’s house for safekeeping. When he brought them up to the house on Christmas morning two girls from the cabins were trying them out to make sure they worked right. They came into the house with their little brothers and sisters to help my sister Faye play with her toys.

We passed around a basket of dried fruit, exotic salted nuts and candy in a large wicker basket left at the house by Mr. Jones, the furniture maker for whom my father worked. The boys wanted to put the Daisy to work on the birds in the pine grove next door, so I went out to show them how well I could aim. There was quite a crowd in the backyard, firecrackers being tossed about—dangerously close I thought—so I took the fellow who liked me best down the hill to find a target.

Drury pointed out a bird perched on a limb and I took aim, allowed a bit for windage and fired. The bird fell and when I picked it up, its little yellow and black head tilted lifelessly over my thumb. I gave the gun to my accomplice and told him he could keep it, sinking my head against his musty chest to hide my tears when he hugged me. That New Testament I worked so hard to get had not done me much good, for I had killed a bird I did not eat, a cardinal sin in my father’s eyes.

The Japanese had bought up all the scrap metal in America and used it to make tanks, battleships and airplanes. With our fleet sunk we needed to find any they had missed. Joe, Harvey and his cousins from the Canal Zone and Drury, the fellow I gave the Daisy air rifle to, formed the "Junior Marines" and went into the fields and barns, even under the cabins, to get all the scrap we could lay our hands on. We made a huge pile of it in somebody’s yard, and the photographer from the newspaper took our picture, wrote down our names and printed them in the paper. I was surprised I was such a little waif, as I was sure I was almost grown and ready to become a real marine.

After Christmas my mother decided I was too old to share a room with my little sister, so we moved to a brick house on 12th Avenue, not far from a wholesale warehouse, where I could buy a box of twenty-four candy bars for eighty cents and sell them for five cents each, netting a profit, if I gave none away and resisted the temptation to eat some, of forty cents. I envisioned great wealth from this scheme, and I knocked on many a door and ruined many a tooth.

On Halloween my mother celebrated my eleventh birthday in the party room at the Coca Cola plant, inviting my fifth grade class, including my rivals for the affection of Phyllis Matheson. She could tear your heart out when she sang "O Holy Night" at our Christmas program at Oakwood. The war had turned with the route of the Desert Fox in North Africa and the sinking of the carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor in the battle of Midway.

My father came home for Christmas and announced we would be going up North when school was out. Johnny Cauble helped me and my sister make a Memorial Park by the creek that separated our house from his. She knew nothing of snakes and I had to grab her hand as she reached for an ugly fellow, coiled and ready to strike, sitting on the bottom of the creek glaring at her. Cotton-mouth moccasins were not welcome in the rock garden we were building as a good-bye present to North Carolina.

Jimmy Jones lived behind our house with his grandmother on our side of the creek. His uncle had taught him about sex and we crawled under his house before I left so I could learn what he knew, but his grandmother heard us laughing and sent me home. I wondered if people could tell when you knew how babies were made. I was afraid to look at my mother when she read from Hurlburt’s that night because she might see that I had lost my innocence.

My older sisters, who dated boys on the high school football team, did not want to go on the train with us when we left, and it was only when my mother promised they could comeback in the fall to finish school that they went at all.

Baltimore was a different world, not at all like North Carolina, but there was no polio epidemic like the one that came to Hickory as we were leaving. Polio had crippled Roosevelt, a man greatly loved in Maryland. I got a job right away delivering newspapers for a friend of my fathers, who had two sons who read the Bible every night before going to bed.

Johnny was sixteen and attended Baltimore City College, where he was the Maryland Scholastic diving champion. I liked his older brother David who lived in West Virginia with his grandmother. He always hit a home run in the bottom of the seventh inning to win the softball game. David went on overnight camping trips with my Boy Scout troop. He could whistle loud enough to be heard a block away and he let me hold his tee shirt when he played softball.

Summer ended and David went back to Marshall College and I started to school at William Paca P.S.#83, a big brick building in the city surrounded by tiny houses with white marble steps which were scrubbed clean every morning. The windows had landscapes painted on the screens, and there was a bakery that smelled like heaven on every corner that did not have a bar selling National Bohemian Beer. The school building was old and smelled like books. The Vice-Principal looked at my report card and sent me to the class of Miss Kathleen Moore, who was a Virginian like my father’s family.

Yankee children had strange names I had never heard before, smelled like garlic and played with a black and white ball they called soccer, bouncing it off their heads and never touching it with their hands. Miss Moore had a reading ladder and moved my name up a notch every time I read another book, and when I got to the top she gave me Pearl Buck’s ‘The Good Earth’ to keep. She did not know I had read all thirty books in the Rover Boy series, and most of those about Tom Swift, a fictional hero a lot like David Conner was a real one.

It snowed a foot on Thanksgiving, and my papers were heavier with all the Christmas advertising. I was afraid the weight would pull my head off and the melting snow soaked my socks so bad my feet blistered, but David’s father counted on me to keep the papers dry and put them inside the customer’s door. I could not let him down, so I missed Thanksgiving dinner. My mother saved me a glass of port to warm me back up when I came home half-frozen.

The war was going better but the Germans kept sinking our convoys so they were launching a Liberty ship a day at the Bethlehem and Fairfield yards in Baltimore. They needed help making bombers in Middle River, so my mother learned how to make them. There was no place to make a Memorial Park so we collected odds and ends and joined with some Pennsylvanians to pretend we were making airplane parts until we were told the place where we played was contaminated and we better stay away from it.

My mother did not have much time to shop but I went with her on Christmas Eve to the heart of the city to shop at O’Neills, Hutzlers, and Stewarts department stores, trying to find a doll for my little sister, but there were none left. I have never before or since seen stores as empty as they were in 1943, and the money I had saved to buy gifts was useless. I knew it was better to have money and nothing to buy with it than having something to buy and not having any money.

Even food was rationed, and we had blue and red buttons we used to buy meat, butter, eggs and sugar. There was also a coupon for gasoline, but the letter on the windshield of my father’s 1942 Oldsmobile allowed us some extra because my parents were helping win the war.

An older boy delivered the morning paper for Mr. Conner, and on June 6, 1944 just before sunrise he woke me up crying "Extra, Extra, read all about it." There was an invasion of France underway, and the maps on the front page had arrows pointing to the place where men were dying. That was the day Miss Moore told me that the principal wanted me to go to a school named after Robert E. Lee on Cathedral Street where I could finish school more quickly if my parents would give me money for public transportation.

I had learned to make my own way in the world besides delivering newspapers. I collected beer and soda bottles, took them to a liquor store that gave me two cents for small ones and five cents for large ones. I borrowed a lawn mower from the rental office and cut the small lawns in my neighborhood for a quarter if inside and fifty cents if it were a corner house. I paid for my own school lunches and my carfare, so I told her I would go.

My scout troop, lead by Mr. Kirby, camped out in Chinquapin Park and later that summer we went to Camp Horseshoe on the Octoraro Creek, up near the Pennsylvania border. I was at home paddling canoes in snake infested waters. The Maryland snakes are not fierce and they swim away instead of swimming after you. My troop leader told me they were not poisonous like the snakes Harvey and I caught. They call them water moccasins but they are just snakes that swim. We sang a dumb song at meals, trying to drown out boys from other cabins, about "our ears being made of leather and flapping in windy weather because we were from Hemlock don’t you see."

Later the Scouts had a Jamboree in Patterson Park and Mayor Theodore Roosevelt McKeldin came to pass out signed pictures of himself. If I were going to spend my life righting wrongs I would have to be a politician, so I watched to see how it is done. When all the pictures were given out the Mayor turned around and looked right at me. He knew I was watching him. He was a big man and he walked over to the fence I was leaning against, picked me up and sat me on it. He asked me who I was, where I was from, and what I was doing. So I made a note to ask voters about themselves, get them talking, a great ice breaker.

I told him where I was starting junior high next week and he tapped me on the shoulder and told me I was going to make my mark on the world. I asked him not to tell anybody because other boys were already jealous. When he asked me why that was, I told him I could run faster than any of them, had better grades, more girl-friends and an older friend who played football, basketball and baseball for his college. I did not want it to get any worse. He promised not to tell anybody, and with a happy shake of his head walked over to the next troop, looking back at me and laughing so hard he forgot to give me his picture.

My junior high was on Cathedral Street opposite the Rathskeller. The building was old and creaky but the teachers were not. Boys Latin school was a block away. When I went to Mercy Hospital to have my tonsils removed, a priest and two nuns holding burning candles were standing at the foot of my bed when I awoke. I feared I might be in heaven already.

Bruce Hornstein found out about my belated circumcision when I bled on my white gym shorts while performing on the pommel horse. Gilbert Hurwitz told me my eyes were hypnotic, and he liked looking at them because they were always changing color. I was afraid of what he might see because my eyes were the windows to my soul.

The war ended in 1945 so delivering the afternoon paper was boring without the daily maps of the shrinking Third Reich on the front page. When I started to high school at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute in September 1946 I bid my customers farewell. They were all in agreement that I should put my education above all else if I wanted to make my mark on the world.

Without knowing if I could afford it I signed up for the college preparatory course. The school was modeled after the Naval Academy in Annapolis, combining practical engineering and drafting courses with college level mathematics, physics, and mechanics. The latter were easy for me, but no matter how high my I.Q, my mechanical aptitude tested off the bottom of the scale. I was not good engineering material.

Kind classmates like Charlie Gerwig and Vernon Brooks helped me through pattern making, metal crafting, blacksmithing and machine shop. We put our wooden patterns in molds, pounded wet sand around them, removed the pattern, melted the metal and poured it into the mold to bring out a casting exactly like the wooden pattern with which we began. It was the only place in the school where I felt at home.

My grandfather Bullard’s Connecticut cousins had a large foundry they used to make artillery for the army, and my mother showed me some stock in their company with her maiden name on it which my father did not know about. I elected to pursue electrical engineering where I had nothing to make, just parts to assemble, to complete my laboratory work.

Having run all my life as fast as I could I tried out for track in my junior year and broke my left arm playing football in November. I was a half-back and I liked vaulting over the tacklers, until some wise guy reached up, grabbed my ankle and pulled me back to earth. I missed some fundamental lectures in algebra, got but forty percent on my exam and had to attend summer school to make up what I missed.

Johnny Conner went to Duke where he became the Southern Conference diving champion, and both he and his brother David went into the air force to fly jet planes when he graduated from Marshall. In December I took an examination to attend the Naval Academy in Annapolis, but flunked the eye examination because I was near-sighted, after which I was fitted for glasses to wear at movies and in classrooms.

My family was adamant that Davidson College, a Presbyterian school near Charlotte was the only place I could go to college. I asked Dr. Chamberlain, the Presbyterian minister who drove me and my blue-nose friends to Washington to attend youth meetings to write a letter of recommendation. He, too, had told me I was destined to make my mark, and he was as angry as a pea-turkey hen when the college said I couldn’t come. He made them so ashamed they offered me a partial scholarship.

Partial would not do, however, and Miss Kathleen Moore, my sixth grade teacher who attended the church where our youth groups met sent me to the Rotary Club for an interest-free student loan. The loan committee had two members from the Franklin Street Presbyterian Church, and their minister of fifty years was Dr. Harris Kirk. His grand-son, Elliott Verner, was a freshman at Davidson. Next to David Conner, I admired Elliott more than anybody else. The committee was kind enough to lend me four hundred dollars.

Unlike loans for college these days, I had to pay my loan back before I graduated. It was a good thing the tuition was only three hundred dollars a year. I returned to the state of my birth to find out where and when and how I was going to make my mark.

Here is a clue. There is a lot I know that I will take to my grave, so I ask that you rely on your skill as a detective to know where and when I learned things I have omitted to protect friends, many of whom are no longer here. I am not seeking to condemn but to inform. If you follow the facts to their logical conclusion, you will see quite clearly when we lost our liberty and became thralls.

Chapter 2.

"How did you ruin your life?"

"I didn’t go to Davidson"

Middle Tennessee State graduate,

February, 1955

At College and University

At age seventeen I got off a bus in Davidson, North Carolina, took one look, decided I hated the place and took the next bus to Mooresville, seven miles north where I called my laughing Aunt Ethel. She took me in, gave me a pep talk, and sent me back the next morning. Davidson was all-male, rigidly controlled by the Southern Presbyterian Church. There was no drinking of alcohol on or off campus, an hour of chapel every morning except Saturday and mandatory Vespers on Sunday night in the college church.

The student body was predominately southern and disappeared on Saturday afternoon, leaving a hand full of out-of-state students alone in deserted dormitories. The next morning I was still determined not to stay, but a preppy classmate sitting next to me was so excited about being there, I decided to give it another day or two.

As freshmen we ate in the college dining-hall, where Mr. Spence served us grapefruit every morning with our orange juice, eggs, bacon and toast. Everyone belonged to a fraternity after the first semester, but assuming I was a Yankee, the North Carolina students did not know me, although my mother had told me plenty about their fathers, many of whom she had dated. I automatically became a member of the Campus Club, a holding place for those who could not afford a fraternity or who had yet to make up their minds. Sigma Chi had sprung from its ranks the year before I arrived and Alpha Tau Omega during my freshman year.

We participated fully in all intramural sports, from touch football, track, swimming, softball, wrestling and the inter-fraternity sing each spring, a competitive songfest in which we had to sing the alma mater, a classical religious piece, and a Broadway musical number. George F. Bason, a graduate of the Hill School, was our musical director. At graduation, George was class salutatorian, going on to Harvard Law, joining a Wall Street law firm before being appointed a Bankruptcy Judge in Washington, where he authored one of the longest legal opinions I ever read.

I roomed with two Floridians my freshmen year in Old East. Joel Mattison was a Phi Gam and a sophomore, while Allan Garrison, a Kappa Alpha, was a George F. Baker scholar from Lake Wales, Florida. Joel later became a doctor and worked at Lamborene with Dr. Albert Schweitzer where he found a wife. Allan, as a physicist, later worked with my brother-in-law, James J. Gallagher when Jim was Director of Science at Georgia Tech.

Everyone was enrolled in Army Reserve Officers Training Corps the first two years and the outbreak of the UN sponsored police action to repel the invasion of South Korea at the end of my freshman year gave it more importance, for a lucky fifty of us would move on to get commissions, thereby gaining deferral from the draft until we graduated and were commissioned second lieutenants of infantry in the Army Reserve.

During the summer I worked as a laborer in the pipe mill at Sparrows Point, alternating shifts every week. The United Steel Workers of America represented the employees and there was a tug-of-war between the Union’s agent to get me in and the Bethlehem plant management to keep me out. I caved and joined when a load of pipe was dropped from a crane on the spot where I was sweeping the floor. The shift foreman had seen it coming and forewarned me. A worker in a union plant who doesn’t carry a union card puts his life at risk.

As a sophomore, I roomed with W. Tucker Blaine, Jr. in Rumple, the oldest dorm on the campus. Donald Schreiber, who later became President of Union Theological Seminary, called it an "arsenal of culture", a term I now apply to my house in Glen Arm. Tucker’s father founded a general insurance agency in Houston in 1910 when the city had fewer than ten thousand residents. He was a director of Houston Natural Gas, later known as Enron. So much old Baltimore money was invested in the company a special car was added to the train in Baltimore to take directors and stockholders to the annual meetings in Houston.

The director I knew best was Fred Singley, a Baltimore lawyer who later became a judge on the Court of Appeals. The Singleys and the Blaines were close friends, and Mrs. Singley attended my church. Fred told me the only time he walked into the Court of Appeals without butterflies in his stomach was the day he was sworn in as a judge on Maryland’s highest court.

Tucker did not make it into third-year ROTC, so he transferred to the University of Houston where he was commissioned in the Quartermaster Corps. He was sent to Korea as an assistant S-4 after the armistice.

We were told when we arrived at Davidson in 1949 to look at the person on either side of us in our assigned chapel seats. If I were there four years later, neither of the men on either side of me would be. That was painfully true, for only a third of us endured to the end, as our numbers dwindled from 375 to 118 before we graduated.

In those days, America’s colleges and high schools were among the world’s best. That is, sorry to say, no longer true. In 1953, Davidson bragged about its homogeneity, its rigid adherence to academic standards and its Rhodes Scholars. Today it brags about its diversity, its selectivity and its mediocrity. Everybody graduates with high marks, but if they have had a Rhodes scholar after our class graduated I would be pleasantly surprised.

I continued working for Bethlehem Steel following my junior year as an expediter at the cold-rolled, steel sheet mill. I worked the day shift, making sure orders were filled on time and accurately. Orders were deemed filled as long as the delivery weight was plus or minus ten percent. The temper and thickness had to be correct, however, and my job was to take steel from an over order, send it to be re-tempered or re-rolled and add it to a short order. While working in the comfort of an air-conditioned office, I did get out into the plant to locate the over order and re-tag it with instructions for the mill to carry out.

Bill Bivins and Tyler Berry, both pre-law students from Tennessee, were my closest college friends. Bill and I were in ROTC, and he later became the chief justice of New Mexico. Tyler was in the naval reserve, which required him to hitch-hike to Charlotte once a week for drills. He was my assigned partner in accounting lab, and our friendship lasted until his death. He was a Sigma Chi, and when I became President of the Campus Club at the end of our junior year, his brothers joked that the Sigs were the only fraternity on campus with two Presidents.

Tyler and I did everything together, including our senior papers in Dr. Lilly’s 18th Century prose class, an elective Bill, Tyler and I took just to test our mettle against the most demanding teacher on the Davidson faculty. Our joint effort earned us both high marks, and Dr. Lilly’s praise. At our Tenth Class Reunion, Dr. Lilly told my wife about our effort. At our Fiftieth Class Reunion, I gave our original papers with Dr. Lilly’s hand-written comments to Davidson’s then President, Robert Vagt, who promised to put them in the college archives.